This is not The End

Why you’re probably wrong about the future of entertainment (and humanity).

This post encapsulates a lot of my thinking about entertainment, culture, society, and humanity in general. It’s very high-level, informed by my fascination with anthropology and evolution, of which I am no expert. If you are an expert, feel free to correct me in the comments. I love learning and being humbled by folks smarter than I. I consider this part 1 of many in my pursuit of a grand unified theory of storytelling.

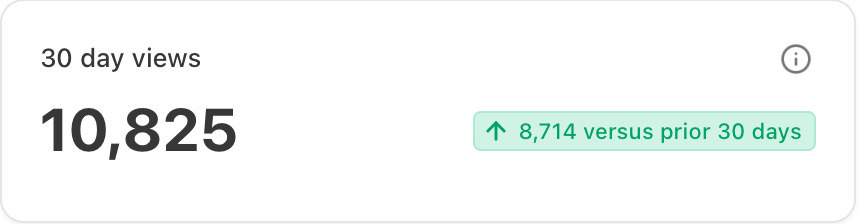

On another note: This Substack recently crossed 10,000 views in 30 days, and it’s all thanks to you: My brilliant and devoted readers. Thank you for helping me reach this milestone. I have some exciting news about the Substack coming next week, so make sure you’re subscribed to stay on top of that.

Correction 5/8/25: I mistakenly cited Taylor Lewis as the source of a quote from her recent post. The quote is actually by Ted Goia.

The Apocalyptics are wrong. The Futurists are wrong. So are the Doomsayers and Fatalists and the AI-powered, wild-eyed Tech Bros.

They’re wrong about the future of entertainment, they’re wrong about the future of art, they’re wrong about the future of humanity.

You, dear reader, are probably wrong.

In the last year or so, I’ve read a ton of articles in traditional media and Substack discussing the future of entertainment, culture and by extension, society as a whole.

I’ve read about how Ryan Coogler’s deal with Warner Bros. represents “the death of the studio system.”

- has written about The Death of mid-budget TV.

- decried the death of the mid-budget feature.

- argues Hollywood could be a ghost town in five years.

- has a terrific/ominous post about billionaires investing in AI and ignoring humanity in which she quotes :

“if ai takes over filmmaking, the entire business will leave hollywood—and migrate to silicon valley. the same is true of every other creative industry.”

Along with so many Ted Hope posts (Seriously,

, are you okay? I’m worried about you.)Outside the world of entertainment, we see innumerable thought pieces on the oncoming “death of democracy” and “the end of reading” and “the end of disease” and on and on.

Some of these predictions are presented through a lens of utopianism, while quite a few more are painted with a much darker, apocalyptic brush. Some are conditional: If this happens, then that will happen.

But the thing that’s stood out the most to me is the sense of finality they depict. They describe humanity as inexorably barreling towards an event horizon that - once crossed - is defined by eternal homeostasis.

Once the tech overlords fully control entertainment, true art will forever be lost under an avalanche of AI-generated slop.

Once wealth inequality reaches a certain tipping point, there’s nothing that can stop its malignant growth.

Once our political adversary is elected to the White House, that’s a wrap on the democratic experiment.

I too have envisioned a dark and perpetual future similar to those depicted here. Hell, I’ve even trafficked in some of these polar thought processes, writing about how “the gatekeepers are dead” and how it’s “the end of entertainment as we know it.”

The thing is: If we have even a cursory understanding about human nature, it becomes evident that these predictions of entropy betray a critical lack of imagination.

True: In the world of politics, there are some places where - even now - people have lived their entire lives under a totalitarian regime. North Korea is a gleaming example of this perpetual darkness.

But I see the hermit kingdom as the exception that proves the rule. Not to mention that power is fickle and forever is a long fucking time.

I believe - I have always believed - the only certainty in this world is change, and that you should always think critically when reading about an imagined future with utopia on one side and apocalypse on the other.

Living on the Extremes

The human brain consumes 20% of the body’s energy while at rest.

Consider that for a moment.

There’s all sorts of physical processes at work in your body at this very moment, from your stomach and intestines digesting food to your lungs inhaling and filtering oxygen to your heart pumping blood through 10,000 miles of blood vessels.

And 1 out of every 5 calories of energy is redirected to the space between your ears.

In other words, your brain is a greedy little asshole.

The thing is: Your brain isn’t wrong to be that greedy. It’s the executive function of the body. Without it, all other organs may as well be processed into Soylent Green (from the movie, not the confoundingly named beverage).

And while your brain knows how necessary it is, it also understands how expensive it is.

Our body (and its CPU: The brain) isn’t aware it’s the year 2025. It’s from an ancient time before written words and history and TikTok.

If you don’t get enough calories to fire electrical signals through the neurons in your brain, you die. And 200,000 years ago, this happened a lot. The brain developed two main ways to economize calories to save itself from starvation:

Consume more - The stomach growls, the brain tells the body: “Need hunt. Move legs. Find elk. Kill eat.” (Or, if you’re a prehistoric vegan: “Gather berries. Lots of berries. Nom-nom berries”).

Do less - Apart from expending fewer calories doing prehistoric yoga (which incidentally also involved killing elk), your options were limited here, because in order to eat, you had to hunt, gather or contribute to the tribe in some visible way.

There was, however, another ace up the sleeve that a human brain had to increase efficiency: Generalizations.

The human brain loves generalizing - and thinking in binaries - because nuance introduces cognitive friction. Thinking about the gray area in between two extremes burns a ton more calories than just saying George W. Bush is “good” or “evil.”

Think of generalizations as a shortcut, a way to catalogue things efficiently. Imagine not having categories like “friends,” “family,” “colleagues,” and not even being able to catalogue people by your main interaction type.

That would be a fucking nightmare.

Of course, there are drawbacks to generalizations. They can often lead to bad things like prejudice and racial profiling.

Additionally, generalizations fail to account for nuance that can dramatically alter context.

Obviously it’s okay to call Frank from Accounting a “colleague,” but sometimes, losing that nuanced gray area has negative knock-on effects. Saying “cholesterol is bad, avoid it at all costs” doesn’t take into account HDL, or “good” cholesterol that has countless benefits in the human body.

Ironically, one such benefit is improved brain function.

In this case, by forgoing HDL, the brain is shooting itself in the foot, which of course begs one of my cheeky stick figure illustrations:

One other major drawback: Things tend to get a bit slippery when we start to apply these generalizations to our predictions.

By combining generalizations and futurology, we’re stacking one imprecise thing on top of another: A non-nuanced view of the world on top of an inexact map of the future. And these inaccuracies don’t just add, they multiply.

That’s why I reject predictions about a possible future that is one way forever. Determinism is the last bastion of intellectual laziness. History doesn’t care about your certainty. It’s messy, meandering and unpredictable, and precious few people have correctly predicted the death of anything meaningful in society.

Of course there are examples of technologies like the automobile fulling doing away with the horse and buggy industry, but - again - these examples remain the exception, not the rule.

Full disclosure: I’m equally guilty of generalizing about the future as any of the aforementioned writers. In fact, we’re all susceptible to this form of prognosticating.

Why this inherent impulse to guess at the future state of things? Glad you asked.

People’s Penchant for Prognosticating

Humanity has been fascinated by obsessed with predicting the future for much longer than there have been crystal balls or horoscopes.

In fact, I’ve argued repeatedly in the past that every single one of us was born with this prediction engine hard-coded in our DNA.

It’s called storytelling, and it doesn’t always come pre-packaged in three-act structure. The earliest stories were likely devoid of a second act finale or a hero’s redemption.

But the development of these proto-stories did have its own inciting incident.

50,000 years ago, during the cognitive revolution, humanity developed storytelling as a means of survival.

Imagine you’re a Homo Sapiens 50,000 years ago. Your tribe has been growing steadily since you found that kickass valley with plentiful game and those wild mushrooms that don’t give you uncontrollable diarrhea.

But in recent months, the game has become scarcer and almost all the non-diarrheal mushrooms have been picked clean. So you hike to the top of a hill and spot deer tracks leading into the valley.

You speculate, based on the tracks and your past encounters with deer, that these tracks belong to a herd of deer this herd will likely gather in a particular clearing at a particular time of day. You rally your fellow tribespeople, telling them that tomorrow, you will trap the herd in the narrow valley crossing so you can pick off the weakest/oldest members of the herd. All of these things:

The speculation of the herd of deer…

The planning involved in trapping them in the narrow valley crossing…

Even the concept of “tomorrow”…

These are all examples of early stories that Homo Sapiens told themselves and their tribes in order to survive, expand and grow.

Side note: If predicting the future represented humanity’s earliest form of storytelling, that means that humankind’s first “genre” was technically sci fi.

Nowadays, prediction is big business, precisely because curiosity is so prevalent among humankind. And curiosity gained such prevalence through evolution.

Early in our history, curiosity became a trait that signified a good mate. I imagine the person who conceived of and executed the plan to trap those deer - after returning to the tribe - had their choice of mates. And I do not blame their mates for choosing them. They sound very brave and handsome and capable of providing for me and my growing family. Let’s get bizzay.

But - as we all know - storytelling didn’t stop there. Not even close.

The Evolution of Storytelling

Biologically, we’re not terribly complex organisms. At least, no more so than any other garden variety megafauna.

We eat, sleep, breathe and reproduce as many other mammals do, and setting us side-by-side with other species of humankind like Homo Erectus or Homo Neanderthalensis, you’d be hard pressed to visually identify what made us all that different.

But there is one thing that our now-extinct human brethren lacked: Stories. We were the first - and thus far only - species to develop the type of abstract storytelling described above.

And while humanity’s first stories originated more-or-less as educated guesses as to the whereabouts of our next meal, humanity has evolved, and so too have the stories we tell. They’ve grown in length, complexity and abstraction.

Instead of serving primarily as a means to help nourish our bodies, stories now also act as nourishment for our souls, lighting up the emotional core of our brain and fueling connection via shared stories that help us build more complex organisms called “societies.”

As Historian Yuval Noah Harari argues in his book Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, complex societies emerged around the same time as humanity’s capacity for storytelling, and - spoiler alert - that’s not a coincidence.

In Sapiens, Harari implies that stories are now everywhere, interwoven into the fabric of society so ubiquitously that we don’t even recognize them as stories anymore. Social constructs are a form of storytelling. So too are governments. And currencies and corporations and law and order and Law & Order.

Without stories, we have no way to talk about these abstract concepts. Without a way to talk about these abstract concepts, they don’t exist. Although I bet Australopithecus would have produced a KILLER episode of Law & Order:

This is part of the reason I don’t think that storytelling is going anywhere, and why fears of AI dismantling or usurping stories from humanity don’t make sense to me. Stories sit firmly in the domain of humanity, and any imagined future of a mountain of AI slop domineering human culture woefully underestimates both humanity and culture.

The Only Constant is Change

On the subject of AI: Every technological revolution in human history has been accompanied by people who fear (and therefore hate) that technology, along with predictions that the technology will undo humanity and doom us to an eternity of this thing or that1.

But apart from the Agricultural Revolution - which brought about the demise of hunting and gathering - given enough time, technologies tend to drift from exotic to endemic with little fanfare. Electricity is technology + time. Paper is technology + time. Even modern Capitalism is a form of technology, pioneered mainly by the Dutch in the 16th Century, superseding a far shittier form of economics: Feudalism.

All this is to say: Changes to society happen in spurts, and every time one of these spurts happen, there are people who inevitably perceive this change as the end of history.

Why does humanity tend to jump straight to this end-state delusion?

This too is human nature! Are you noticing a pattern start to emerge? I really hope you are.

How People Perceive Their Future

A study I found in Science Magazine argues that people maintain a fundamental misconception about their future selves.

In it, they discovered that - for groups spanning 18 to 68 years of age - people of all ages described more change in the past 10 years than they would have predicted 10 years prior.

In other words, almost all people across all age ranges tend to underestimate future change. This phenomenon applies to individuals estimating the outcomes of their own lives, but because individuals are part of a larger organism, it also extends to society as a whole.

The study concludes that people “regard the present as a watershed moment at which they have finally become the person they will be for the rest of their lives.”

What I’ve noticed is that people tend to project this expectation of future stasis onto a society that couldn’t achieve that stasis if their lives depended on it.

Chaos, change, growth… these things are as much a part of humanity as storytelling.

In George Orwell’s dystopian sci fi 1984, Orwell imagined a future where a singular world government (but really several world governments in cahoots) kept the globe in a constant, steady state of ignorance, slavery and war.

This dystopian future of stagnation and suffering is best summed up in a quote from the 1948 novel:

“There will be no curiosity, no enjoyment of the process of life. All competing pleasures will be destroyed… If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face— forever.”

It’s great sci fi but not a realistic portrayal of how Homo Sapiens operate.

Especially not in America. We are a nation of rebels, and any attempt to stifle human change and growth here will be met with pitchforks and rolling heads.

Look: I Get It…

It’s easy to read headlines about the encroachment of AI or Big Tech or Fascism or runaway Capitalism and think: This is it. This is how we end up under the boot.

Whether it impacts the art we make, the stories we tell, the connections we forge with others, our lives and livelihoods, what’s more horrifying to us is that sense of finality.

I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve thought the very same.

And of course history doesn’t happen without participants. While change is a natural function of the human experience, people who refuse to accept the status quo are often the ones accelerating that change. These people are the real heroes of our human story.

But when we think in binaries, when we remove nuance from our vocabulary, when we level predictions of the end of history, we end up doing a disservice to our complex storytelling engines and the delicious calories that fuel them.

Stories aren’t going away. Neither is human creativity, or human connection or the human tendency towards adaptation and growth.

I spend a lot of this Substack arguing that the entertainment industry is undergoing profound change. But I’m also increasingly convinced that whatever emerges from this period of change will be anything but permanent. It won’t satisfy the dark doomsaying of the pessimists or the wild fantasies of the optimists. Nor will it represent a new normal, but rather the next chapter in our ongoing story.

The patterns of history suggest we’ll adapt, evolve, and find new ways to tell our stories, just as we have in the past.

So when someone tells you that AI will end storytelling or that streaming will kill cinema or that some other technological innovation represents The End of Everything We Know, acknowledge their work, sure.

But also understand that they’re just telling you yet another story.

They can’t help it. It’s in their DNA.

Stay tuned,

Jon

On the flip side, there are usually also manic supporters of the technology, and right now, those supporters are talking about how AI signifies the end of work, the end of disease, the end of suffering. I believe that they too are deluding themselves using the same stories described above.

If you feel cheated, see below for the missing illustrations:

A very good reminder and some much-needed counter-programming.

VERY glad those illustrations were found, another informative (and fun) read !!