How Not to be UnFunny

An Intro to Writing TV Comedy that Isn't (*sigh*) "Horse Testicles"

EDDIE

What do you see in that guy?

JESSICA RABBIT

He makes me laugh.

–Who Framed Roger Rabbit

Thanks to for convincing me to publish using the NSFW placeholder subtitle. I hope you’re happy.

I Miss Comedy TV…

I know I sound like an old fucking codger when I say that I miss comedy TV, but I really fucking miss comedy TV.

I miss caring about a character and watching her stumble through absurd scenarios that would never happen in the real world. I miss that feeling of being blindsided by funny moments that I never saw coming.

Mostly, I miss there being a robust ecosystem of TV writers’ rooms where all the weirdos and misfits could convene to make each other laugh so hard they shoot pamplemousse Lacroix out their noses.

Of course, there are shows that call themselves “comedies” and yes - a couple of them still manage to make me laugh. But, as I describe in my post Comedy in Crisis, the volume of shows that can legitimately call themselves comedies is in hasty retreat.

This is a problem, and for a very long time now, I’ve wanted to be part of the solution.

I don’t claim to be an expert in writing TV comedy, but I’ve spent around 10,000 hours in TV Writers’ rooms alongside some of the funniest writers on this planet, and I’ve learned more from them than most humans will ever know in their lifetimes.

This post was born of a recent inquiry I sent out to writers from various organizations and groups, asking for comedy pilots for potential optioning.

After reading nearly 100 scripts (at least 5-10 pages of each), I noticed writers making the same comedy writing mistakes over and over again.

A lot of these mistakes are ones I made when I was younger, and one or two of them I still make today. All that is to say: Don’t beat yourself up if you recognize your writing in this post.

Comedy is really hard. Narrative comedy is harder. Narrative comedy on TV is possibly the hardest.

But - it’s not impossible.

In this episode:

🎭 Why "making people smile" isn't the same as making them laugh - and the one true test that separates real comedy from feel-good moments

💀 The wordplay trap killing your scripts - why puns and alliteration make readers roll their eyes (and how to avoid "comedy jail")

🚫 Why jokes are your enemy - the counterintuitive truth that TV comedy doesn't come from dialogue at all

🔥 Where real TV comedy actually comes from - how Joey's clothes and Selina Meyer's tantrums actually work

📢 The preaching problem - why having a "message" can destroy comedy and how to hide your worldview in plain sight

🎯 The specificity superpower - how Harvard vs. "college" and Rottweiler vs. "dog" can increase your comedic surface area

Comedy Context

If you haven’t read Comedy in Crisis, please do. It provides some crucial context on the state of TV comedy today.

Go ahead, I’ll wait.

Consider this a companion piece to that one.

Where that one outlined the “what” and “why” as in: “what’s fucked with the TV comedy landscape?” and “why does it matter?,” this one outlines the “how” as in: “how do we un-fuck it?”

This piece provides practical lessons for making your script as funny as it can be. It’s targeted towards early-career writers, but can serve as a refresher for more experienced writers as well.

Hopefully, after reading it, you’ll possess a robust framework of how to make a TV show (or anything, really) more funny.

But even if you’re not that into comedy (I’m looking at you,

) there are lessons here that extend to writing any form of entertainment.And who knows? By the end of this, you may have a newfound appreciation for all the things that make us experience the communal, life-affirming touch of the divine that is laughter.

I’ve chosen to structure this as a listicle because it’s easier to write and read, and also because listicle sounds like someone cross-bred the words “list” and “testicle,” and that always puts a smile on my face.

Note: I paid for these lessons with thousands of hours of labor and verbal abuse that way you don’t have to. And all for free!

The least you can do is subscribe, share or comment (or all three!).

So buckle up, chuckle-fuckers. It’s about to get real.

Lesson 1: Only Laughter is Laughter

Cracking a smile is not laughing

Snapping your fingers is not laughing

Nodding your head thoughtfully is not laughing

Being moved emotionally is not laughing

It seems ridiculous to specify these things, but I feel I have to.

To be sure, you can do any of the above and make people laugh, but too few people seem to understand this basic premise:

Only laughter is laughter.

For more prescient insights like this, be sure to…

Being able to elicit a “You go, Jon!” is very different from saying or doing something actually funny.

The true barometer of comedy is quite simple: Does it take over a person’s senses and force air - the thing that keeps us all alive - out of their lungs in uncontrollable, violent and prolonged spasms?

Not to mention the fact that if you do it really well, people may laugh so hard that they end up crying or, better yet, peeing themselves a little. As Katie says: “Fluid leakage is a measurable sign of comedic success.”

My wife, ladies and gentlemen.

The ability to consistently evoke laughter is no less than the ability to control someone else’s body (albeit for a few seconds at a time).

Master this skill and you transcend your mortal form and become a living god.

This is the elixir of life that many of us spend our entire existence seeking, and, as I allude to in Comedy in Crisis, it’s not a common skill to possess.

By the way, if you want to be the type of writer that composes grounded, thought-provoking scenes that aren’t all about the laughs, that’s great! In many ways, it’s a more noble pursuit than the type of writing that I aim to do.

But if you want to knock the wind out of people with laughter, that requires a commitment to a different - if parallel - set of skills.

Action Items

Get Feedback

Ask someone you trust to read through your script and add a checkmark next to a joke only if they laughed out loud at it. Be clear that you want brutal honesty - smiles and chuckles don’t count. The checkmarks (rather, the empty spots on the script) are your roadmap for punch-up.

Lesson 2: Puns aren’t (that) Funny

To the extent that you laughed at “chuckle-fucker” at all, it’s probably way more about the attitude with which the words were delivered than the actual words themselves. I harbor no illusions about these turns-of-phrase being at best cute and at worst: 🙄.

Still, many writers I’ve read use puns and wordplay in their scripts and conflate it with comedy. But readers - and audiences - lack the same context that made those words funny to you, and without that context, puns don’t do what you think they’re doing.

I’ve worked with a number of Showrunners who are utterly allergic to puns and ban them in their writers’ rooms. Pitching clever wordplay in these rooms will earn you a scowl and land you in what I call “comedy jail,” an expression that is not funny unto itself, unless you explore exactly what it looks like.

Of course, there’s room for the odd pun here or alliteration there, but for the most part, steer clear.

And I’m very sorry to say: “The joke is that it’s not funny” is not funny.

We’ve all seen someone roll their eyes at a dad joke, so unless you can find a truly unique way to spin it, avoid this cliché if possible.

Action Items

De-pun-ify

Find all the puns in your script, select them, and hit “delete.”

Harsh? Maybe. But if you remove all the puns and wordplay from your script and you’re left with no more “funny” moments, you have a big, big problem. At the very least, you have a problem of variety. Go back to the drawing board.

Distinguish Cute from Funny

Something can be “cute” or “clever” but don’t mistake it for “funny,” and understand why you wrote these moments at all. Something can be cute and funny, but just because it’s one doesn’t mean it’s the other.

Lesson 3: Jokes Are Your Enemy

Repeat after me: TV Comedy. Does. Not. Come. From. Jokes.

But how can that be true? After all, comedy scripts are made up of jokes (or at least they should be), right?

Wrong.

Fucking wrong.

Go directly to comedy jail, do not pass go, do not collect unemployment, you boneless jellyfish fuck.

Scripts are made up of characters and relationships and attitudes and goals and story beats and conflict.

You only have a script if you hear how these characters speak, feel the tension between two ex-lovers, cringe at their view of the world and lust after the next twist in the story.

Jokes - the things people say in response to the events of the story - are a side quest at best.

In The Office, “That’s what she said” carries no comedic weight without the manic, wild-eyed enthusiasm of Michael Scott’s delivery of the words.

This illuminates a reality that is very scary for a lot of the TV & film writers I know:

The words on the page cannot be a trusted delivery mechanism for comedy.

Meaning: If changing the specific words in the script fucks up the comedy, the comedy was never that strong in the first place.

Action Items

No Standup Please

Carefully evaluate the dialogue in your script. If your characters sound like they’re reciting a standup routine, get rid of it, fucking pronto, and replace it with something more attitude-driven (more on that below).

Ask a Neutral Party

Ask a trusted colleague to point out their favorite jokes in the script, and ask them what they thought was funny about it. If they can only think of “jokes” in dialogue, you have an issue.

Okay. So if comedy doesn’t come from words, and it doesn’t come from puns and it doesn’t even come from jokes, where does it come from?

Thank you for asking.

Lesson 4: Attitude is Everything

“I can’t remember ever using a funny line in a picture. The characters become funny because of their attitudes, because of the attitudes that work against what they’re trying to say.”

–Howard Hawkes (via

)It bears repeating:

Attitude is Everything.

Comedy comes from attitude, and attitude comes from character. That is why the words on the page are fungible.

If your characters are solidly developed, the words matter much less than each character’s relationship to the other characters and to the world around her.

There’s a common misconception about sitcoms: A “Situation Comedy” is funny because of the ridiculous situations depicted therein.

This is false.

It’s only in how characters react to these situations that makes something funny.

See

’s wonderful post on attitude being the lifeblood of comedy. She’s referring to standup, but it applies equally to narrative comedy.Joey wearing layers upon layers of clothes isn’t funny on its own. It’s only funny because of the reckless abandon with which he enters the scene and because he knows the reaction it will elicit from his friend Chandler, which is, predictably: Horrified.

It’s Joey’s unexpected (but perfectly believable) attitude that serves as the comedic engine of that scene, which is a classic example of something called “block comedy”. I’ll go over block comedy in a later post, so be sure to subscribe for more:

It’s only funny because we know their relationship and we understand how Joey is behaving to subvert it. The clothes are just the vehicle for this subversion.

In Veep, Selina Meyer’s tendency to throw tantrums when things didn’t go her way is funny because of the schism between her station and her childish attitude.

Action Items

Bolster Attitudes

Examine the characters’ attitudes in each scene. The quickest way to boost comedy is to amp up attitudes. Instead of Character A being upset that Character B lied to them about their shitty comedy script, have Character A be furious / homicidal.

You can always tone this stuff down, but one of the best pieces of advice I got from one of the most talented comedy writers I’ve known is to “swing for the fences,” since you likely won’t be given a second chance.

Bolster Stakes

When in doubt, look closely at your characters’ goals and why they have them - (AKA the “stakes”). If these things aren’t strong enough, your characters attitudes will feel flat. The more your character wants something, the stronger attitude they’ll have when something / someone gets in their way.

Raise Internal Conflict

Make sure your characters’ internal conflict matches or exceeds their external. For characters to grow (the goal of all good storytelling), there should be some friction between what they think they want and the actual reason they want that thing. This tension fuels comedy just as much (if not more) than their external obstacles.

Get Serious to get Funny

Per Howard Hawkes, characters shouldn’t be taking up screen time cracking jokes. In fact, some of the funniest scenes I’ve seen (and worked on) were scenes where the characters were taking themselves so seriously it hurt. By giving your protagonist a strong goal and entering every scene dead serious about achieving it, you’re setting yourself up for success.

And if you want feedback on your writing, please message me. I’m happy to steer you in the right direction.

Lesson 5: Stop Preaching

This is a big deal, and one of the easiest ways to fuck up comedy.

True: The best stories are about something more than what we see on the screen. They’re about the human condition, or society’s over-reliance on technology or late-stage capitalism run amok.

When we write stories, we inevitably impart these stories with our own worldview, and the lessons foisted upon the hero (or anti-hero) are ideally the same lessons we want the audience to walk away with, too.

I would never discourage someone from telling impactful stories that aim to make the world a better place, especially in such challenging times.

But a lot of writers - including working, produced writers - seem to think that the best way to do that is through blunt force.

If your goal is to move people towards a particular way of thinking, the worst thing you can do as a writer is have your character go on a diatribe about what’s wrong with the world.

If you understood human psychology just a little bit, you’d understand exactly how counterproductive this is.

In Wired for Story, author Lisa Cron cites a study that points to an ineffable fact:

People are more receptive to morals / life lessons when they are hidden within a story as opposed to stated outright.

She goes on to explain that even if people agree with your message, they hate being preached at, and any attempt to do so turns off audiences against said message. Not to mention that it also breaks Rule #1 of visual storytelling: “Show, don’t tell.”

It’s the same way for comedy. Stating your message upfront may get people to nod along in agreement. But while they’re nodding along, guess what they’re not doing?

Pooping.

I mean: Laughing.

If you want to speak your truth in plain, direct terms, start a Substack.

If you want to tell compelling stories that make people double over, then you’d better learn to couch those messages in subtext or - better yet - character attitudes.

Subtlety is your friend here.

Action Items

Marry Lessons to Story

Step 1: Understand your message; what you want to say about the world.

Step 2: Make the world of your story agree with you.

If your story is about a woman trying to Climb Everest, and your lesson is “It’s not the destination; it’s the journey,” that woman should learn that she doesn’t need to reach the summit, lest we completely invalidate that lesson (however trite it is). If the lesson is baked into the story itself, you won’t feel compelled to state it in dialogue.

Show, Don’t Tell

Instead of having a character talk about wealth inequality, show a tent city cropping up outside of a wealthy gated community. A picture is worth a thousand words, but it’s also way more palatable to the audience.

Leverage Subtext

If you must use dialogue, find ways to hide the messaging in subtext. When in doubt, think “Secrets & Lies.” This also helps increase the tension within scenes, which is great for comedy.

Lesson 6: Be Specific

Every writers’ room I’ve worked in was very different from the others. I worked on an animated sitcom for Fox, a prestige live action show for HBO, a YA multi-cam sitcom for Nickelodeon…

But the one thing that they all did well was applying specificity to characters and dialogue.

Characters

A character who “went to college” is very different from a character who went to Harvard. Someone who has “a pet” is very different from someone who has a pet dolphin.

Each layer of specificity you add to a character enhances their depth. And when you deepen a character, you expand the opportunity to find funny touch points between that character and the story / other characters.

Think of all the new things we ended up learning about Richard in Veep, who - by the end of the show - turned out to be a military vet who specialized in animal husbandry and never masturbated until Season 6.

To put it in geometric terms (because I know so many of you are mathematicians): Using specifics to deepen a character expands their comedic surface area.

Dialogue

Specificity makes the things your character says more evocative. Another great Caroline Clifford post on that here:

Again - this applies equally to narrative comedy. Ideally, if you’re unable to show something with visuals, you should be evoking it with specific dialogue.

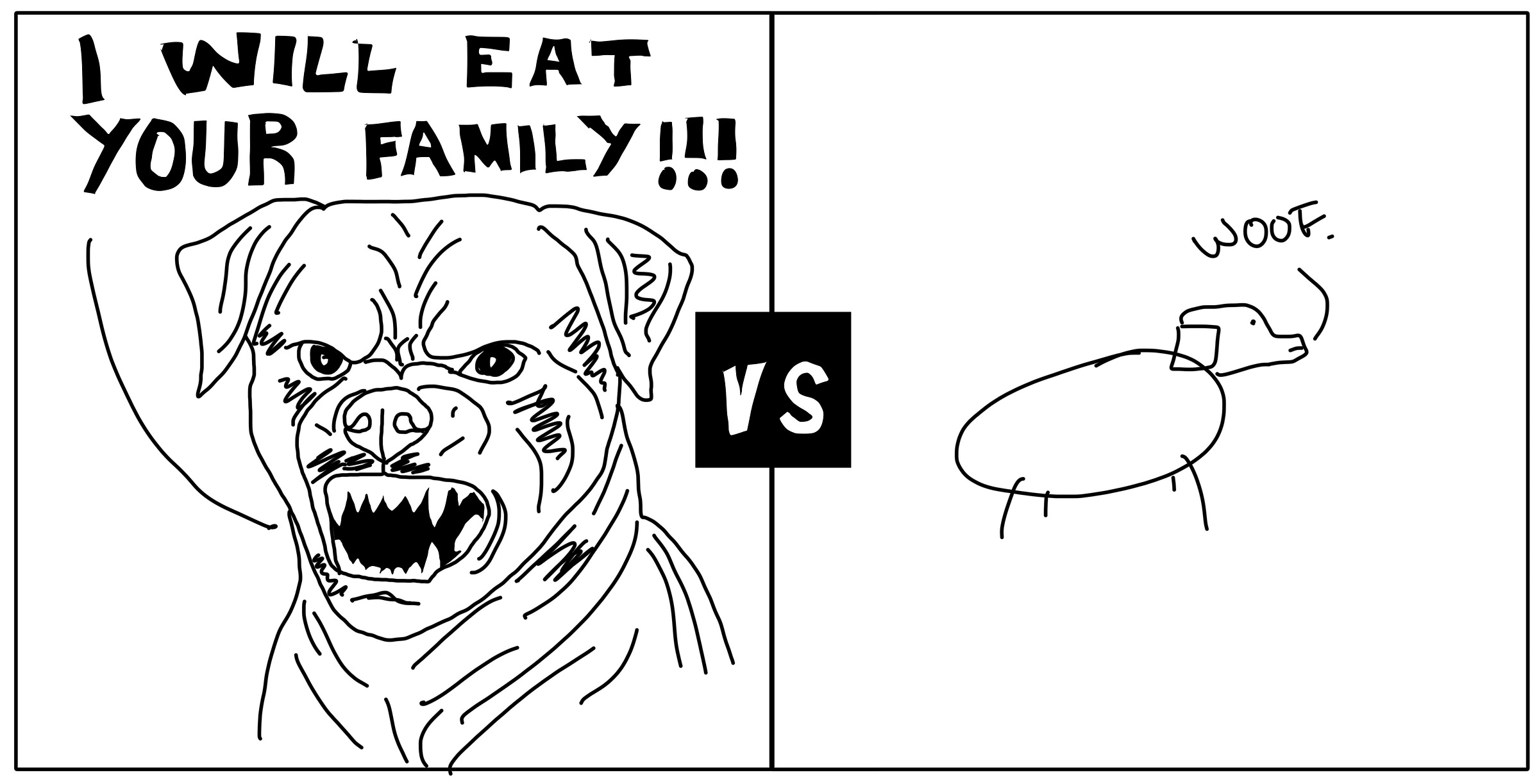

A character saying they got chased by a dog evokes a different visual depending on whether that dog was a Rottweiler or a Chihuahua (#TheDarkKnight).

Specificity vs. Details

Please note: Details are not the same as specificity.

Specificity seeks efficiency in language whereas details disregards it. You can keep adding more details about a car and eventually you’ll get to the point, or you can just use the expression “a rusted-out 1987 station wagon” and that achieves the same goal in a fraction of the time.

Specificity is functional. Details are extraneous. The difference between the two is the difference between “more” and “more precise.”

Action Items

Do a dialogue “specificity pass”

Find language in the script that is generic and think of ways to heighten the specificity of language.

Do a character “specificity pass”

If characters feel flat, find the specific things about them that make them unique and fun. Think back to the most interesting people you’ve met in your life and steal specific aspects of their personality or elements of their life to feed into the character’s backstory. If they learn you used those things, they’ll be flattered (or they’ll sue you, so like, watch out or whatever).

Making people laugh is one of the noblest things a person can pursue.

Jessica Rabbit didn’t fall for Roger because he was “clever” or he “had important things to say about society.” She loved him because he was able to make her do what no one else could.

Ideally, you now have a few more items in your comedy toolbox to write scenes that knock the wind (or other fluids of uncertain origin) out of people.

That’s what we’re all chasing.

So go. Transcend your mortal form. Make people pee themselves. That’s the real power of comedy.

Stay tuned,

Jon

John: Great post!!! I laughed out loud several times. Hope all is well with you.

Great article this week Jon! I read a lot of comedy pilots and it's really hard to get me to pee myself, but it does happen occasionally.